![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Larousse Accident Compost Pit Slap Sotton Old Woman Solange

Bigoudi GGauthier Twins Pen Infanticide

Conversation Unclear Casino Threshold Michel Bombay

About Laure Acknowledgements Autrefois Go-top

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

For proper viewing please use Firefox as your browser, so larger images will resize in frame.

Neither Microsoft Internet Explorer nor Google Chrome will automatically resize large images in frame.

Click on the images below to view large size. Use the back button on your browser when going between

a large size picture and this page, so you do not lose your place on this page.

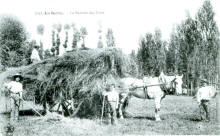

Not long ago, not so far away, on the same planet, a man was judged by

the quality of his works; a woman, by the way she ran her household. No

one was unemployed. There was more work to do than there were hands to

do it.

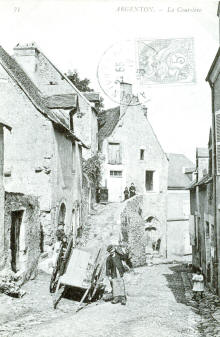

In the town, there was electricity but no running water. Most

people had a garden behind their houses and, also, a small vineyard or

piece of a forest. Wood and coal were the only sources of energy. In the

village, people were craftsmen or shopkeepers.

In the surroundings, the people were farmers with a few cows and

pigs, hay and wheat fields. Some families were only tenant farmers or

sharecroppers. There was no electricity, running water or sewer systems

on the farms. They had a well, candles or kerosene lamps and went to bed

at night knowing what they had to do the next day to sell their

surpluses at the Friday market. Women made butter and cheese, clothes.

They wore women’s clogs around the farms and store-bought shoes on

Sundays to go to church, for weddings, dances and funerals.

There were many festivals with decorated chariots, parades and

dances. Those who lived in the village could go see a movie once a week

in the back of the largest café, where men also went to play cards and

drink the local rosé wine after the weekly market. There were also cafes

in the kitchen of many houses, such as the local barber and bakers.

Each craftsman belongs to a guild—the masons, the carpenters, the

wine-makers, those who worked metal (the farriers, the clock-makers) had

a guild responsible for a festival. The town had a municipal band of

volunteers who would play at each festival and give a concert in the

town hall once a year.

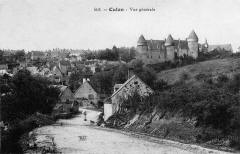

Chateaumeillant, Cher -- Berry, France circa 1950

For proper viewing please use Firefox as your browser, so larger images will resize in frame.

Neither Microsoft Internet Explorer nor Google Chrome will automatically resize large images in frame

Click on the image above and the images below to view large size. Use the back button on your browser when going between a large size picture and this page, so you do not lose your place on this page.

There were two times—BEFORE THE WAR TIMES and AFTER THE WAR TIMES—and

they were spoken of as such. BEFORE THE WAR meant the way our

forefathers had done. AFTER THE WAR meant the American way, i.e., the

mechanization of agriculture thanks to the Marshall Plan, tractors

instead of horses and oxen, harvesting machines instead of your

neighbors with scythes and cycles, flattening the landscape for large

machinery instead of planting hedgerows, barbed wire instead of

honeysuckle and blackberry hedges. Mechanization changed everything and

took command—cars, trucks, vans. everywhere—supermarkets competing with

farmers’ markets.

The rapid expansion of this non-indigenous transformation created

an immediate division between those who could afford it and those who

could not. Small farms disappeared, old trees were uprooted to flatten

the land for the easy movement of machines, country roads were paved.

The landscape itself was transformed; landmarks, iconic sites, spiritual

and historical anchors disappeared.

What happened DURING the war is under the regime of BEFORE. The

landscape has not changed. People have taken sides. Some support the

Vichy government—the merchants, the pious, rich farmers. The majority—

the workers, the poor farmers— support and are in the Resistance

(covertly, few overtly before 1943).

This small town had been a Roman stronghold known as

MEDIOLANUM—MIDDLE OF THE LAND. Now, how did the Romans know that? No

wonder we—the ones they called the HAIRY ONES—were impressed by

everything they did. How could one (200 years BC) measure a country? The

Romans did—and accurately. The present-day marker indicating the

geographic center of France is not very far away from Mediolanum—known

today as Chateaumeillant.

It is said that it was a Roman officer from Mediolanum, France

who founded MEDIOLANUM—MILANO—in what is now Italy, after his return to

his homeland.

The town has a small museum housing the artifacts found on the

site and the surrounding areas by farmers plowing or digging wells and

foundations. There is even the burial site (a tumulus) of a high-ranking

officer. It is not a pretty town—houses of grey stucco are stuck one

next to the other along one main street going North-South with a zigzag

in the middle. On a rainy day it looks dismal, sad, even ugly (like most

French towns of the 18th century). But if the visitor knows how to get

lost in the countryside, he will find the medieval—even Roman—vestiges

of its past, the charm of a shy and delicate Nature, the landscapes of

George Sand and the “Grand Meaulnes”, the swamps of AVARICUM, the

Cistercian Abbey, the habitat of the many legends, its history.

The town is on a hill, which allowed the Romans to overlook the

countryside around their camp. Tunnels dug below their camp lead to all

sides of the surrounding areas and were large enough to move men,

animals and equipment. The remnants of these tunnels still serve today

as cellars for the town inhabitants.

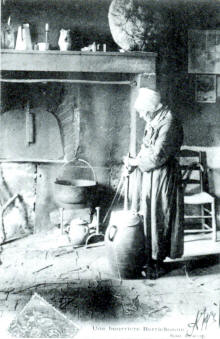

As in most villages and small towns in rural France before World

War II, there was no running water, no sewer systems. There was

electricity in the towns and villages but not in the hamlets. Farms were

situated near wells. so water had to be drawn one bucket at a time. No

plumbing systems, no bathrooms, no faucets anywhere, no sinks.

There were outhouses, always a distance from the farm, usually

past the wood pile so the users of the outhouse could bring back

firewood for the chimney, where cooking was done. Usually, there was a

brick and stone oven in one wall, fired once a week to make bread and

bake pies and other delicacies. Very few farms had wooden stoves to heat

the room besides the fireplace.

Most farms had only one room with a bed arranged against the

wall, a long table with long benches on each side. The beds, high off

the stone floor, were enclosed in tents of heavy flannel attached to the

ceiling from a large brass ring. Those curtains kept in the heat from

the bodies and gave a measure of privacy to the occupants. The cloth was

often red.

A family consisted of one or two grandparents, their son or

daughter, and the grandchildren and the farmhands, often a couple and

their children. The land was inherited or was leased to sharecroppers,

poor peasants who shared half the products of the farm with absentee

owners.

Women knew how to knit and sew clothes. Only men’s work clothes

were bought and they lasted a lifetime. Linen was a part of the woman’s

dowry and lasted more than a generation. They were often of hand-spun,

hand-woven cotton or linen. They were washed by boiling in large tubs or

a tripod placed on a fire outside in the courtyard, then taken in a

wheelbarrow when cooled to the nearest stream for beating with a paddle,

then rinsed in clear running water. Diapers, women’s sanitary napkins

were treated the same way. Once rinsed and wrung, the laundry was spread

on the hedgerows of honeysuckle or blackberry to dry.

There were two schools, one for boys and one for girls, that all

children had to attend until the age of fourteen. Farm children had to

walk miles each day to come to town on foot. Some stayed with relatives

or other families in town during school days. All children had an hour

and a half for lunch, since they often had to go fetch water at the

three pumps in town during their lunch break. The water was carried in

tall metal containers with one handle on the side, called brocs, that

carried about two gallons.

Only a few families in town had radios or wind-up gramophones.

There were only 5 telephones in the village: the post office was number

1, the gendarmerie was number 2, the two doctors were numbers 3 and 4,

and the veterinarian was number 5. Each hamlet had a telephone in the

café or small post office, from which you could call another post office

and tell the operator at what time you would be there to place a call to

another person. A boy on a bicycle would relay the message to an

isolated farm and the correspondent would ride on horse or bicycle to

the post office or telephone to be there at the appointed time.

When sick or in the need of a doctor, patients would just appear

at the doctor’s door or be brought in. Persons with chronic illnesses

would wait for Fridays to visit the doctor after the weekly market and

before going to the cafes.

There was one church and one cemetery. Bells would toll loudly

enough to inform everyone of funerals or weddings. Those who could

afford it paid women to go door-to-door to announce funerals and also

“weepers”—women who moaned loudly behind the coffin.

Communications from the town hall to the people about elections

and meetings were made via a drummer who went from neighborhood to

neighborhood, hamlet to hamlet, beating a roll from his drum to attract

attention and then reading the notices in a large voice. Since he had a

large area to cover on an old bicycle, it would often take several days

to deliver messages. He was rewarded with generous quantities of wine to

clear his throat after each reading and was obliged to sleep in ditches

or barns at the end of the day. Bigoudi was our town drummer and the

best-known alcoholic—of which there were many, since wine was easier to

get from a bottle than water from a pump or well. But he was part of our

landscape and accepted as such.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Larousse Accident Compost Pit Slap Sotton Old Woman Solange

Bigoudi GGauthier Twins Pen Infanticide

Conversation Unclear Casino Threshold Michel Bombay

About Laure Acknowledgements Autrefois Go-top

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

LAROUSSE

Chateaumeillant, Cher, France 1937-1945

When I asked Suzanne the difference between a village and a hamlet, she told me that the hamlet was smaller than a village and did not have a church. That answer disturbed me because Jean Sablon, popular crooner of the 20s, had been singing: “Il est une église, au fond d’un hameau, dont le fin clocher se mire dans l’eau, dans l’eau pure d’une riviere.” So, a hamlet could have a church. Or could it? It bothered me. Papa, who was really my grandfather but had brought me up with Grandma and Suzanne since I was eleven days old, was God. He therefore knew everything worth knowing.

So, I asked him the difference between a village and a hamlet. He

immediately pulled out Volume I of the 1929 Larousse Universel (the

latest) and spelling the word loudly several times read the tome’s

entry: German origin, related to the English “home”, a group of a few

rural houses not incorporated into a larger town. So, there you

were—church or no church. Larousse did not say. But Suzanne could not

say “no church.”

Grandpa took the opportunity to make me repeat the spelling over and

over again—H‑A‑M‑E‑A‑U. The rhythm suggested a tune that formed in my

head and I went back to Suzanne in the kitchen singing H‑A‑M‑E‑A‑U and

telling her, bragging about the meaning of the word according to the

highest authorities of the time, Papa and Larousse.

Growing up, Larousse was our entertainment. Although we had a radio, a

huge thing shaped like a gothic church, there were very few broadcasts

and it was only turned on for news. In the evening my sister and I would

look through the 2 tomes of illustrated Larousse, perusing through the

colored plates of animals, paintings, costumes and industrial

inventions. It made us dream of exotic places, things we did not know

but knew existed elsewhere.

Our grandfather, whom we called Papa, had gone to Madagascar

after the First World War to study tropical diseases, since many of our

soldiers had come from the then-French colonies. He had seen some of the

animals pictured in the Larousse and could vouch for their existence. We

even could see the photo of Grandpa and Grandma in Tananarive. Africa

was the most exotic place we knew of, and we invented games based on

what we knew of the continent. We even pretended that our toy dog was a

monkey and our small blue wooden elephant was roaming an equatorial

forest on the floor of our bedroom. We made a tent with our bed sheet

and chairs and called it our camp in the savannah. Oh, what a few

pictures in a Larousse can do!

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Larousse Accident Compost Pit Slap Sotton Old Woman Solange

Bigoudi GGauthier Twins Pen Infanticide

Conversation Unclear Casino Threshold Michel Bombay

About Laure Acknowledgements Autrefois Go-top

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Accident

Chateaumeillant, Cher, France 1937-1945

Although he lived a couple of days after his accident – in a coma – Monsieur Demenois did not survive the crash of his Rolls Royce in front of the castle in Culan. His chauffeur, Etienne Leblanc, did.

Other men had died there, in the deep ravine.

Nothing very unusual about that.

But a Rolls Royce had never been seen before.

So the car was what people talked about.

The beauty, the size, the comfort of the machine.

Even as a wreck it imposed awe.

The vases of cut glass inside, between each door, had not even

been broken. The white

roses had fallen out --the vases had remained affixed in their golden

loops. Something worth

talking about. Vases in a

car! The local inhabitants had heard of, or seen in magazines, Delages,

Talboots, Delahayes but an English car?

Never. As to

Monsieur Demenois, it was quickly learned

that he had been born in a small town south of Culan.

His mother had been

a servant in the small manor house of a local minor nobleman. The local

farmers called the place “the chateau” since it had a medieval tower on

one side and was surrounded by a large forest.

By local standards it was an imposing structure with slate roofs

and was impeccably maintained.

From the main road only the roofs and the top of the tower could

be seen. Yet a very

unassuming, private place as most of the manors in Berry were.

It had been assumed long ago that the child of Ninon Autissier had been

fathered by the viscount and no one thought more about it.

Philippe Autissier grew up as a small child in the “chateau,”

among several others belonging to the other servants and day laborers.

His mother continued her work there, mostly as a cleaning woman.

At age six Philippe was sent to boarding school in Chateauroux.

He was a tall boy for his age, good looking, intelligent and

disciplined. On holidays he

would come back to visit his mother and play with his childhood friends.

Although better dressed than his play-mates, he never flaunted

his advantages over the children of farmers or share-croppers.

He was very affectionate with his mother, although his unusual height,

like the viscount, gave him a natural air of aloofness – not

superiority. His mother, after all, was just a servant.

When Philippe reached his twelfth birthday the viscount sent him

to Paris to a boarding school where Latin and Greek were taught.

Philippe made a few trips from Paris to visit his mother before her

death when he was eighteen.

He was seen at the local cemetery where she was buried in a simple grave

with a small marble marker.

The Viscount died ten years later and the chateau abandoned.

After receiving his baccalaureate he was sent to Paris to continue his

studies. After that he was

never seen again in the region.

His mother Solange died sometime during the war and the property

was sold to a local farmer and is now the summer residence of an

Englishman.

From Etienne Leblanc we learned that Mr. Demenois was a very rich

industrialist, that he was a widower and that his destination was a

small hamlet near the town of Chateauroux.

News travels very quickly in small towns.

No need for newspapers, which few people read at that time and

were delivered by the local bus several days later after the fact.

Newspapers and magazines were dropped at the “papeterie”, the store

where one could buy small books, postcards, notebooks and other school

supplies as well as candies.

A small notice was printed the following week after Mr. Demenois’ death

mentioning that he had been born and raised in the small town of Culan,

which by that time everybody knew.

Two lines in the obituary section.

No one saw Philippe again until the chauffeur of the Rolls-Royce

revealed to the authorities – and therefore everybody – that Monsieur

Demenois was a rich industrialist who had made a fortune in steel and

that he was on his way to an isolated farm near the chateau of L.M.

Six months after the death of Philippe Demenois, a Parisian lawyer

arrived at the farm of Solangelette Autissier to inform her that she was

the legal and only heir to Mr. Demenois’ fortune.

It seems logical to assume that the twenty-seven year old farmer

must have been surprised – or had her mother, Solange Autissier or her

mother’s parents told her that her father was Philippe Demenois?

We do not know.

Solange Autissier had been seventeen when she met and fell in love with

Phillippe Demenois at the local fair.

Solange was a very pretty girl and a very good, natural dancer.

Solange is a very common name in Berry.

It is the name of a saint.

History or legend, one or the other depending on your faith, says

that such a person existed.

Her mother and grandparents had died by that time and she was running

the small farm she had inherited with the help of a retired – because of

injury to a leg – mailman living in a nearby hamlet.

They intended to be married once the harvest was done.

He was older than she was but was a good, simple man, reliable

and of clean habits. They

intended to stay in the small, one-room farm with its stable, hay

barn and outdoor well and outhouse.

His chauffeur, Etienne Leblanc, received several fractures and a

concussion. He remained

many weeks in the hospital in St. Amand and it is from him that we

learned the story.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Larousse Accident Compost Pit Slap Sotton Old Woman Solange

Bigoudi GGauthier Twins Pen Infanticide

Conversation Unclear Casino Threshold Michel Bombay

About Laure Acknowledgements Autrefois Go-top

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The Compost Pit

Chateaumeillant, Cher, France 1937-1945

It was the year of the “Débacle”.

The Maginot Line, thought impregnable, had not been breached. It

had been bypassed.

The German Army had

simply gone around it and was coming from the North. First, we saw

French officers in cars driving south, then the foot soldiers, those who

had gone to war with flowers in their guns to fight the war to end all

wars, singing “Y’a Hitler sur la ligne Maginot.” Now, the French army

was walking it did not know where, heads down, eyes vacant, hungry,

dirty, stinking, dragging itself like mangy dogs, begging for food and

water, hugging walls in case of enemy air-attacks.

We watched, as stunned as they were.

Our courtyard was full of soldiers, washing at our water pump,

eating all of Grandma’s canned fruit and vegetables brought up from the

cellar.

All the yards were full of the remnants of an army. When they

moved on, on orders given by someone, they would be replaced by more of

the same. For many days, on and on went this disorganized parade of

shuffling, creeping, wounded men, called “La Déroute”.

One day, as I was taking food in a small metal pail from my

grandparents’ house to my Great-Grandmother’s for her dog—just stale

bread soaked in the hot water we poured over the plates before washing

them, just to give the bread a little taste—it was snatched from my

hands by a hungry soldier. I kept saying, “But it’s for the dog!” and

the soldier had replied, “But I’m hungry too.” I was shocked—shaken and

deep down humiliated by the sight of a man gulping down dog soup without

a spoon.

Then, one day, the “defile” stopped. There were no more men.

Where did all these poor men go?

The larger town—where I had been in boarding school, since our village

only had a primary school—had been bombed, so I had been brought back to

attend the small girls’ school and given additional tutors for subjects

not taught there. The village—small town, just under 1900

inhabitants—also had a boys’ school at the other end of town. Some of

the children came to school every day from isolated farms or hamlets

after a one- or two-hour walk, most in wooden clogs without socks. In

wintertime, some put straw in their clogs to keep warm and carried a hot

brick wrapped in a towel against their chests. Lucky ones had heavy

hand-knit socks, caps, and mittens.

We did not look down on the poorly dressed and shod children who

sat next to us town children because there was some sort of awe in front

of their unstated stamina, dogged perseverance, the straightforward

demand for equal treatment in their eyes. They did every day a task we

could not imagine, we town softies. Besides, some of them had shown to

be our intelligence equals. Some of these children really smelled very

badly of cow manure and other potent odors, but we accepted that, along

the smell of chalk and ink permeating the classrooms. Even dirty

children do not smell as bad as unwashed adults. Children do not

perspire as much, I guess. Or because they do not drink wine as much as

grownups. We did drink a little wine with our meals, and, in wintertime,

coming home from school half frozen, we were given a big bowl of half

wine-half water, warm, with sugar and spices. That did not prevent the

chilblains that we had on knuckles and knees, but it warmed your

chest—the most important part of the body, we knew—for a few hours,

enough time to do your homework. War or no war, heat in the house or

not, enough food or not, enough light or not, there was always homework

and wine. Wine was more common and plentiful than food: everyone knew

how to make it, and the vineyards always produced more or less grapes,

but always enough.

There was to be a math test. I did not like math, pretty close to

hated it. I was not good at it. It was too dry for my taste, and you had

to write down all the theorems learned by rote in the left hand margin

of your geometry problems. Even one word left out was counted as a

mistake.

So, I had to think of a way to avoid taking the test and came up

with the idea of breaking a leg. Grandpa, the doctor, would have to put

my leg in a cast and probably make me rest a few days in bed, as he did

recommend with broken limbs. If I did not manage to break a leg, I might

break an arm—the right one, preferably, since I was right-handed—or had

been made to be, since left-handedness was not acceptable then.

No problem. We had, in a corner of the garden, a large compost

pit. It was made of cement, about eight feet long and five feet wide. In

it, Eugene, the gardener and my grandfather’s orderly since the First

World War, threw the manure from our chicken coop and rabbit hutches, as

well as all the debris from the garden and the kitchen.

I

conceived the idea of jumping from one end of the compost wall to the

other. I was very agile, but this was a long leap to make and surely I

would hit the opposite wall with one part of my body or another. Before

going to school, the day of the exam, I went to the garden, sure of

determination and guarantee of success, and after pumping my legs as

before a sprint, leaped off the cement wall.

I did hit the wall—a little—but only with my forehead and fell

inside the warm composted manure. I must have screamed, unbeknownst to

me, because Eugene and his wife Suzanne, who helped Grandma with the

housework, came running and yelling, “Look what she has done now!”

I was carried into the house, washed, re-clothed, and brought to

my grandfather’s surgery room where, without a word, my forehead was

painted with a burning iodine, then bandaged. By now, I had a bump the

size of half a grapefruit but no broken bones.

I was ashamed, embarrassed by my stupidity, and worried about

what would happen next.

With his pale blue eyes burning into mine, Grandpa just said, “No

harm done. Don’t you have an exam today, young lady?”

And that was that. Feeling defeated, like those soldiers in “déroute”, I went to school with a pain in my head, a bandage on my forehead, and my pride, situated somewhere in my mid-section, churning.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Larousse Accident Compost Pit Slap Sotton Old Woman Solange

Bigoudi GGauthier Twins Pen Infanticide

Conversation Unclear Casino Threshold Michel Bombay

About Laure Acknowledgements Autrefois Go-top

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The Slap

Chateaumeillant, Cher, France 1937-1945

It was the summer of ’41. The town where I was in boarding school (I had

been in boarding school since the age of 6) had been bombed, so I had

returned to my grandparents’ village. My grandfather had found

tutors—Monsieur Fradet for Latin and Mlle Perronet for English and

French.

I now know that Mlle Perronet, a retired grammar school teacher,

did not know English well, but I liked going to her house, which she

shared with another retired teacher, Mlle Fusibet. I had heard

deprecating rumors about these women and had told Grandpa, who had

replied that these ladies were honorable and their lifestyle was

nobody’s business. Mlle Perronet could play the piano (a little) and

managed to teach me “Ba Ba Black Sheep” and “Oranges and Lemons” over

the course of the summer. Mlle Fusibet tended the large garden where

we would often walk, dictionary

in hand, to learn the English names of plants. But we never made a

sentence with them, so I always forgot them.

Monsieur Fradet lived on the outskirts of the village at the top

of a very steep hill. His house was surrounded by his small vineyard,

kept in weedless condition. He taught me Latin, gave me lessons, and

made me recite my verbs and declinations.

I did not like going to Monsieur Fradet’s house. The hill was so

steep I had to dismount my bicycle before reaching the top, out of

breath—bicycles had only one gear then. My lessons were in mid-afternoon

when the heat was at its worst.

That afternoon I had gone to a small meadow on the outskirts

where we kept Ponette, the horse that drew my grandfather’s buggy, since

there was no gasoline for his car. I knew daisies grew in the ditch by

the hedgerow. Also, honeysuckle and blackberries.

No one in town had a wristwatch. A few men, like my grandfather,

had pocket watches at the end of chains tied to the buttonhole of their

vests and kept in a pocket. But the town hall had a very big clock that

struck the hours, the quarters, and the halves. It could be heard

everywhere. And I heard it strike three. Time to go back home, mount my

bicycle, and go to my lesson. But I was having such a good time and was

carrying an armload of daisies. And it was cool in the ditch.

The idea occurred to me to pretend that I did not hear the clock.

Grandpa was rarely home during the day, going on his errands to take

care of his patients and returning only at the end of the day for

dinner.

I stayed in the meadow and returned only around four for the “gouter”,

the four o’clock snack. The front door was, in fact, two, joined by a

large metal bar with a sculpted knob in the middle. When both sides were

opened you could bring in a stretcher. I came in with my flowers only to

see Grandpa coming toward me in the corridor.

“Where have you been? Don’t you have a lesson with Monsieur

Fradet? Don’t you know the time?”

“No,” I said.

Instinctively, I backed up against the door, guilt rising from my

feet, paralyzing me on the spot where my back touched the door and the

left side of my head touched the metal doorknob. I could easily see that

Grandpa was furious. His voice was angry, loud, uncontrolled. It was so

I was carried, dragged, escorted by the two women and made to sit

on a stool next to the operating table. The wound was cleaned and

dressed, no stitches. And I now had a bandage around my head.

After all the necessary was done, Grandpa said: “Now go to Mr.

Fradet and apologize.”

I was speechless. My head throbbed. It was still hot, and I was

not thinking of the fact that I would miss my gouter too, but I dare not

disobey Grandpa.

Angry, ashamed, hurt, Grandpa, Grandma, Suzanne watching me, I

mounted my bicycle, left the house and rode in the direction of Mr.

Fradet’s house, up that stiff hill.

I was stunned. Stunned by the depth and ferocity of Grandpa’s

anger. “Why? Why?” I kept asking myself. Sure, I had lied. I knew the

time, had heard the clock. But he had never slapped me before on the

face. Occasionally, Grandpa had hit me on the buttocks, but usually I

was given a lecture, his eyes piercing me like lances, and that was all.

Like the time I had been caught by Eugene trying to drag a ladder

from the garage to get to the roof after having seen a picture of a

parachute. The intention had been to put the ladder against the wall of

the woodshed, climb up with an umbrella, and jump down with the umbrella

opened. All the ladders were made of wood then and were very heavy, so I

had not gone very far when Eugene, grandpa’s orderly/aide/gardener and

Suzanne’s husband, met me and asked me what I thought I was doing. Proud

of myself and my knowledge, I told him my intentions, and, of course, he

in turn told Grandpa. That fostered a long lesson on gravity, the speed

of falling objects, the distances needed to brake the fall as in a car,

a bicycle, etc…etc…and a spanking on the buttocks to add weight to the

discussion lest I forget.

Eugene and his wife Suzanne had the right to discipline me

whenever they felt I needed it. Which was quite often. I was very

mischievous, although I thought at the time “adventurous” a better

description of myself.

They kept a cat-o’-nine-tails whip in the kitchen where one or

the other could find it most of the time. The whip had a wooden handle

and a dozen or so, maybe nine, long leather straps, about an inch wide.

It was kept on top of the hutch, so I could not reach it even if

I stood on a chair (I had tried). It stung when it hit your calves, but

Eugene or Suzanne never hit very hard, although it left marks on your

skin for a couple of days. Of course, in those days girls never, never

wore pants, even when there was a foot of snow on the ground. Pants on

women led to lewd behavior, smoking, driving cars, and inevitably to

immoral conduct (meaning fornication outside of wedlock). It seemed that

every sin led to fornication, the ultimate, unforgiveable offense with

the worst consequences now and in the thereafter.

I made it up the hill and arrived at Mr. Fradet’s house to find

him in his vineyard, a copper sprayer strapped to his back. He saw me

and my bandage and asked what happened. Was I going to tell him that I

had gotten the beating of my life for having tried to avoid coming to my

lesson? No, no, no. So, I lied again and answered that I had fallen off

my bike, all the time trying to imagine whether Grandpa could possibly

know what I had just said.

Mr. Fradet then told me that it was too late for my lesson, that

he had to continue what he was doing because the sprayer tank was almost

full and he had to finish it lest it thicken and clog the sprayer line.

I should go home and enjoy myself.

I was furious. I could feel my veins engorged with blood. The

pain in my head was knocking so hard behind my eyeballs that my pupils

were out of focus. Now I knew what “seeing red” was. I had gone to all

this trouble, pain, effort to get here, and the old man did not even

care. I had been made to feel guilty for nothing. That was not fair.

That was not just. That was not human. That was not...

Coming back down the hill, coasting, had always been a pleasure.

The air in your hair made you feel (a little bit) like those aviators

who did tricks with their machines at the air-show in Chateauroux, the

big town 46 km away. Or you could soar like the geese that flew twice a

year above the town on their migrations to far away countries, even

continents, across the Mediterranean Sea to Africa. The thought, as well

as the physical contact with rushing air, gave you goose pimples.

Cleared the acid juices out of your stomach and tangled wiring in your

brain.

Why had Grandpa done this? He was not an impulsive, violent man.

As I was free-falling down Main St., known as the Grande Rue, the

only “rue” in fact, I began to put the elements of my misfortune

together:

First—Your word is your word. You say you are going to do

something? You do it.

Second—You do not lie to Grandpa. He knows when you are

lying, as when you said you did not know what time it was.

Third—Mr. Fradet is as old as Grandpa. You respect your

elders, no matter what. If an elder expects you, you go. He may also

need the money he receives for teaching you.

Fourth—I have the same name as Grandpa. The family’s name,

honor, reputation, were at stake. Can’t sully that.

I was rearranging, analyzing the arguments, asking questions and

giving answers as Grandpa had taught me to do, riding full speed back

towards home. Before I entered the courtyard, I had my answers. Grandma

greeted me with a tall, cool glass of lemonade and an aspirin. I knew

that I was already forgiven. The lesson, however, still echoes 80 years

later.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Larousse Accident Compost Pit Slap Sotton Old Woman Solange

Bigoudi GGauthier Twins Pen Infanticide

Conversation Unclear Casino Threshold Michel Bombay

About Laure Acknowledgements Autrefois Go-top

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Mr. Sotton

Chateaumeillant, Cher, France 1937-1945

I do not know whether I could find the way to Mr. Sotton's house in the

forest. I had never gone there by myself. I was a child then. But I

would like to think that if someone pointed me in the right direction I

would find my way. The way birds do. First the small dirt road, on the

right it was, in the middle of the forest. Then perhaps a mile farther

in, with ditches on both sides, the uneven ground, you suddenly came to

a clearing. And there it was on the right, in the center of the open

space. A square house made of stone with two steps in front. Inside,

just one room. A chimney, a table and two benches, a bed, an armoire.

Just one room, almost square, with only two windows, one on each side of

the door.

There was no electricity, no running water;

the well was outside in front of the house. On the left side of the

clearing was a large barn, larger than the house, with a stable for a

horse and a wagon. To the left of the door to the house was a small

plank supported by rough wooden legs on which stood a basin, pitcher,

and a cake of soap. On the wall had been nailed a broken piece of

mirror. This is where Monsieur Sotton washed and shaved. Although he had

a thick grey moustache, the rest of his face was clean shaven.

And that is where I saw a man shave

himself for the first time. A man without a shirt, with suspenders

dangling to his sides.

My grandfather used to be shaved twice a week by the village

barber, who would come to the house and use a folding, long-blade razor

that would be kept sharp by rubbing on a long leather strap attached to

a chair. My grandfather's shirt would be covered by a large towel, and a

round china basin with an indentation for the neck on one side would be

placed under his chin, to receive soap and water.

Not so with Mr. Sotton. After soaping his face, he used a

small-handled razor that he himself ran up and down his cheeks and neck.

When finished, he simply splashed more water on his face, then threw the

soapy water on the ground.

I was spellbound and fascinated and realized that the whole

experience, due to the simplicity of the house and to the act of shaving

alone, outside, in the middle of the forest, bare to the waist, was

something more natural, more elemental than the same function performed

in a bourgeois household such as ours. We had many rooms in our house:

living room/dining-room,

kitchen, offices, waiting room for my grandfather's patients, bedrooms,

bathrooms, corridors, inside stairs, and balconies and, outside, garage

and sheds.

Here, at Mr. Sotton's, everything was compact, reduced,

distilled, minimalized. It was not a house but a refuge against the

elements. Its solidity exuded safety, tranquility. And then it occurred

to me that Mr. Sotton's house was like his torso—strong, square,

straight, not lean yet with no extra fat, and of a color acquired by

outdoor work, often in the sun without shirt. The house may not have

been comfortable by town standards, but it made you feel comfortable, at

ease.

The space told you, "faites comme chez vous".

There were no restrictions here, nothing to watch out for as in

the houses of the village ladies my grandmother went to visit. In those

houses, I had to stay still in my chair while the two women chatted

about things I did not understand or was not interested in. I was warned

in advance to watch where I put my feet (not on the chair rungs), not to

touch anything, and not to squirm in my seat.

My eyes would occupy the time looking at the objects on the mantelpiece

--the clock, the shells from First World War cannons, the photograph of

a deceased man in uniform. Mme Garnier husband?

I had never been told whether she had been married. She had always

looked like a widow to me. But why have shell casings on the

mantelpiece? They were not pretty objects. They must be

souvenirs, I thought then - souvenirs to remember the war. People

were always talking about the war -veterans like my grandfather were

everywhere. The "Great War" they called it and yet my grandfather always

talked about the horrors of it. The mud in the trenches, the

stench, the lice, the lack of medicine, the horrible wounds from shells.

A souvenir? A reminder of some event, someone?

Sometimes, if I were lucky, there would be a painting or a reproduction

of one, a seascape, a landscape, something to get lost in until the

visit was over.

At the house of Mme Gamier, I was

given a cherry with stem marinated in

alcohol with sugar in a pretty little

glass. I enjoyed that but at other houses was bored. Here at Monsieur

Sotton's, there was no boredom possible. There was too much to be seen,

heard, smelled. The comfort was

overwhelming, like being wrapped in

a big comforter. No pretense—it was just itself. You did not have to say

"May I?" before sitting down. You just did what the others did: swing

one leg over the bench, then the other.

And there you were with your elbows on the

table, something you would never do at home. And it felt good.

His house looked like him and he

looked

like his house. They suited each other, were an extension of each other.

When Mr. Sotton had finished shaving, he slipped his suspenders

back on his shoulders and we all went in to have a glass of wine,

mine mixed with water. We sat on the benches on each side of a long

rough-hewn table, Mr. Sotton, my father and me, and the friend who had

driven us there in a car. My father made the arrangements with Mr.

Sotton for the use of his barn, where my father, a painter, wanted to do

some large paintings. A small bed would be installed in a comer of the

barn, next to the horse stall for warmth. That was all.

My father would share Mr. Sotton's food.

Mr. Sotton was the forest keeper, the warden. His responsibilities

were to keep the forest healthy and keep away poachers, clear dead trees

and maintain the road.

He was allowed to kill all the game he could eat,

gather all the mushrooms and plants he needed, and sell the cut dead

wood.

After my mother's death when

I

was six, my father had felt the need to isolate himself to heal his

pain. My grandfather had known Mr. Sotton and his wife before he became

a widower. My grandfather had attended Mme Sotton in her terminal

illness and knew of the peaceful existence of the forest keeper, his

gentle straightforwardness.

My father spent several springs and summers there, visibly

healing his mind and body.

My grandfather and

I,

who lived half an hour away, would often go to visit. Mr. Sotton had a

cocker spaniel by the name of Tarant, which is the first word,

the rallying call, before the hunt. The dog was as gentle as his master

and it was a pleasure to play with

him.

There was also an owl, without a name,

that

stood perched on a small gate closing the path to a pond. The bird just

stood there, waiting for Mr. Sotton to bring bits of meat. I was

fascinated by the way it moved its head from side to side, pivoting half

a turn on its neck.

Although its eyes were enormous, I was told

that it could not see well in the daytime.

It

also had a strange smell, not pleasant. It was free to roam at night but

simply chose to spend its day there on the gate, waiting for Monsieur

Sotton' s offerings.

On May Day, the holiday honoring working people, the custom was

to go in the forests to gather lilies of the valley, in bloom at that

time.

It

was an outing of mostly young people, the lily of the valley being

associated with courtship. Girls and young women went in groups.

Anything else would have been regarded as too "forward", unbecoming.

Young men also went in groups.

It

was an occasion to meet par hasard, to check each other out. An

occasion to say next time one met, "Oh I saw you in the forest, remember

me?"

For days afterwards, the schoolteachers' desks would hold many

bouquets of lily of the valley in glass jars, and the room traded its

usual smell of chalk, erasers and needing-to-be-washed

clothes for the sweet smell of the little white bells. Enough to make

you dream of the forest and the people you had seen there.

Some especially.

Then, it was already a place young people wanted to run away from. Dull,

boring, nothing changed in two hundred years. Nothing to do in spare

time. But it was a place where older people who had gone to live in

cities wanted to return to. For the peace and quiet, the soft look of

its rounded hills, its small hamlets, unchanged in two hundred years.

For the young, there was no sense of privacy. Everyone knew

everyone else, what they did—or were supposed to be doing—where

and at what time. Any change in schedules or places was immediately

noted and broadcast. "Where do you think she could have been going at

this hour?", one neighbor would ask another. The question would make the

rounds of the small town until a logical, plausible answer was found.

And if not? Well, young people will be young people. Remember? And you

wondered who she was going to meet at this hour and where.

Where

was often the banks of the lake-pond-swamp,

called the hang because it did not run all year.

It

was a very large pond formed by the damming of a swamp. On the dam

passed a road. One side of the road, opposite the pond, was much lower

than the water side, and a small house of stone had been built there for

the man who controlled the metal gates and sluice that maintained the

water level. Farmers would back up their

oxen driven carts into the pond to fill barrels with water to irrigate

their fields.

One could walk around half the pond and lie in the grass under

huge poplars. The opposite half was lined by a dozen small houses. But

one could also walk toward the water source, about a mile, and find

oneself on a narrow path with the waters clogged by water lilies and

reeds on one side and high hedgerows of blackberry and honeysuckle on

the other.

Once in a while,

there would be a man fishing but only in the deeper part of the lake and

there was no reason to go up a path that led nowhere.

Unless-of

course, you would have been the one embarrassed if you had gone there to

spy. Therefore, it was a logical place for lovers to go—a safe place,

since one couple was not likely to report on another.

Still,

it would have been nice to have a private life, to have been able to go

unnoticed anywhere, to wear clothes of one's choice, to fix one's hair

as one pleased, to know that there were more movies than once a week—in

proper theatres, too—not in the back room of a cafe, full of smoke, with

an old projector that broke the film several times

each time it was used, and where you had to go accompanied by a parent

or another adult the way you did when there was a dance, in the same

cafe, in the same room that had been transformed into a dance floor by

making wax shavings from an old candle to make it slippery.

There was a fee to be paid to enter the dance, since it had a

live orchestra. An accordion, a drummer, and a saxophone usually made up

the band that played polkas, waltzes and passo-dobles (a form of

simplified tango), sometimes a fox-trot.

There were no windows

in that back room, only a door that was kept opened for the heat that

quickly became intense.

The smell of body heat, added to the odor

of clothing impregnated with the scents of cows,

milk, hay,

tobacco, was as intoxicating as the

sweating hand of your dancing partner on your back.

Marie-Rose and I watched through the open door, fascinated,

studying the dancers' steps and moves. We were quite conscious of our

peeping, of our emotions. Peeping, like eavesdropping, was strictly

taboo, but peering into a public place was tolerated (after all the door

was opened),

provided that you did not stay too long. Time and place was everything,

and they always came together in acceptable or objectionable fashion.

Here, at the door of the cafe,

glaring, probably with our mouths opened, it was like looking at that

Japanese fan my grandfather had bought for my grandmother on one of his

trips to Bourges, the largest town in Berry.

On the fan, an artist had painted the scene of people having tea, seen

through the clouds of cherry trees in bloom. The eye would penetrate the

branches to partially—only partially—reveal what the persons in the

bungalow were doing.

There was mystery there, the fascination of discovery. On the dance

floor, it was to discover what kind of shoes the dancers were wearing,

what kind of clothes. Slowly putting together the elements of what

looked like pleasure. Adding up the pieces of the puzzle that

constituted that desirable picture of dancing couples.

When I was finally allowed to go in at age fifteen (with my

grandmother on a bench on the sidelines), my early impression of

Paradise was confirmed. Since I was a good dancer, I rarely had a rest

and my grandmother enjoyed herself, too, watching me dancing correctly,

the way she had taught me in the kitchen since I was five years old,

standing on her feet, holding her by her arms, lowered, while she sang

some tune from 1900.

Young men and women who did not need chaperones would often

disappear from the dance floor, and everyone would know what it meant,

talk about it, assess the prospects of a lasting relationship, point to

the good and bad points of each partner, agree, disagree on imagined

possible future developments. Most people did not have time to read

books or newspapers. We were our own tabloids.

After the war, running water and sewers were installed in the

whole town and its nearest farms. Many older people who had gone, years

before, to work in larger cities, returned. They bought old houses and

remodeled them, installing "modern" kitchens and bathrooms. At the same

time, automobiles appeared. Every house had a car, every farm a truck,

tractor, machines to separate the cream from the milk,

butane stoves. Farming methods changed.

Hedgerows were removed, old trees were uprooted, land flattened to

enlarge fields and make it smooth for tractors and harvesters, ancient

stone houses destroyed.

Some places do remain the way they were two hundred years ago.

They are known to those who were born earlier or lived in the area.

Others have become tourist attractions, beautiful places to visit-under

supervision—with large parking lots for buses and cars, sometimes with

hotels and inns

nearby.

Monsieur Sotton has been dead for more than half a century, but I

have been told that his house is still there in that clearing in the

forest. Someone probably lives

there today.

But I will not disturb the new occupants, nor will I

try

to peek, even if I could find the way.

The memory of the place, the man who lived there more than

seventy years ago, must remain safe.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Larousse Accident Compost Pit Slap Sotton Old Woman Solange

Bigoudi GGauthier Twins Pen Infanticide

Conversation Unclear Casino Threshold Michel Bombay

About Laure Acknowledgements Autrefois Go-top

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The Old Woman and a Goat

Chateaumeillant, Cher, France 1937-1945

When I was a child and asked what I wanted to be when I grew up, I would

reply, “An old woman with a goat”. Everyone thought that to be a

sensible answer.

In Berry before WW II, there were many old women who knitted

woolen socks for sale. They were often seen sitting in ditches while

their goat, tethered to their leg by a rope, browsed in the hedgerows of

blackberries and honeysuckle. That way the hedgerows were trimmed and

the goats fed. One woman, Madame Chirade, was the one who sold my family

our winter socks, and we knew her well. Madame Chirade would come to our

house to take our measurements once a year. She carried no tape or other

instrument. Instead, she used a string with a knot at one end and

wrapped it around our closed fist. Apparently, the circumference of a

fist is equal to the length of the owner’s foot. She would make another

knot where the two ends of the string enclosed our fists. That was all,

but it fascinated me, and that was part of the reason why I wanted to

grow up to do that. But the other reason, the main one, no doubt, was

the goat. I loved goats and dogs. There are lots of goats in Berry.

Their milk makes many cheeses famous. Valencay, Crotins de Chavignolles,

and hundreds of others that are sold on market days in every village or

small town.

Docteur Guyot

in her living room

My real father and mother were, at the time of my birth, living on a

barge on the Seine in Paris. My father was a painter, which had been

accepted by his parents after several known artists were consulted and

had declared that my father had talent. The problem was the barge—no

electricity, no running water, no heat, no sewer. That was too much for

my bourgeois grandparents (grandpa was a doctor). They were convinced I

would die in that environment, so I was taken away without discussion.

The fact that my mother was a foreigner, a Canadian Native American,

must have played a role in the decision. But I think that the most

important, of course unstated, factor was that grandma had had only one

child (my father) and wanted another. Grandpa had been born into the

bourgeoisie. His father had also been a doctor. But Grandma was the

daughter of a very poor railroad worker with nine children. On his walk

in the native city of Montluçon, Grandpa had seen his future wife on the

threshold of her tenement building, falling in love on the spot. The two

eloped to Bordeaux, where he finished his medical school and my real

father was born.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Larousse Accident Compost Pit Slap Sotton Old Woman Solange

Bigoudi GGauthier Twins Pen Infanticide

Conversation Unclear Casino Threshold Michel Bombay

About Laure Acknowledgements Autrefois Go-top

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Rainulfe and Solange

Chateaumeillant, Cher, France 1937-1945

In the 19th and 20th centuries, many Berichons

named their daughters Solange after the 9th century martyr

and saint. In 1877, a small pamphlet had just been written by L’Abbé

Joseph Bernard on the life of the young shepherdess killed by a young

nobleman, named Rainulfe, for refusing his advances. According to the

Abbé Bernard, the young woman, from a very pious, poor family, was

grazing her sheep near St. Martin d’Aubigny when a young man on his

horse came upon her and was stricken by her beauty, her innocence and

grace. Solange told Rainulfe that she was wedded to God and could not

answer his demands. The nobleman came back to the fields where her sheep

grazed, each time pleading with her to accede to his love, finally

offered to marry her, to share his castle and wealth. Solange did not

yield and always answered the same way, “I am married to God and,

therefore, cannot marry you.” On the 10th of May, 880,

enraged, Rainulfe took out his sword and severed her head. According to

Abbé Bernard and the legend that followed, she picked up her head,

carried it in her arms and dropped it in the nearby fountain, while

saying, “Jesus, my spouse, here I come.”

Today, on that spot, a sculpture of Solange stands, as well as a

small chapel, visited each year by thousands of pilgrims, mostly of

Portuguese origins, who may have conflated the legend of Solange, who

was canonized by the Church, with that of Our Lady of Fatima. The

sculpture shows a young woman without a head, with a sheep also with

severed legs, at her left.

The legend survives and is believed by many Catholics. Many

believers still name their daughters Solange. The writer George Sand,

who wrote many books on the lives and beliefs of pre-industrial Berry,

also named her daughter Solange. George Sand’s manor and hamlet at

Nohant are still standing and receive many thousands of visitors each

year.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Larousse Accident Compost Pit Slap Sotton Old Woman Solange

Bigoudi GGauthier Twins Pen Infanticide

Conversation Unclear Casino Threshold Michel Bombay

About Laure Acknowledgements Autrefois Go-top

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Bigoudi

Chateaumeillant, Cher, France 1937-1945

Some of the older folks in the village may have known his name. To

everyone else he was Bigoudi—a joke, perhaps, since he was bald,

although he always wore an old cap. Or he may have had a full head of

curls when he was young. When we knew him, he was of indescribable age.

But old.

He was small, very thin, sun-tanned, had no glasses and no teeth.

He wore the kind of jacket and trousers that all workmen and farmers

wore, made of a royal blue, heavy cotton that used to be made in the

town of Nimes in the south of France—hence, denim in English. Except

that Bigoudi's suit was no longer blue. It had become grey with a hint

of pale blue—an optimistic sort of grey, not the sad, pale, mouse grey

that children in mourning had to wear for a year. The black mourning

clothes of an adult were perhaps considered too harsh for children, too

sad, painful.

He was the town crier, since in those days few had radios. He

went from farm to farm on an abandoned grey German bicycle, bringing

news from town hall about electoral campaigns, agricultural association

meetings, news of births, deaths, marriages, gossip. On his back,

Bigoudi carried a small drum attached like a knapsack by two straps, and

he kept two small sticks in the jacket pocket (along with his tin of

bicarbonate of soda). Upon arriving in a neighborhood, he would

dismount, drop his bicycle on the ground, take his drum and sticks, and

beat a roll—the kind to signify attention—hear ye, hear ye. After

several doors or windows had opened, he would take out the notice in his

breast pocket and read, slowly but loudly. His speech lacked clear Ts

and Ds, but it was understood.

Bigoudi was also the town public alcoholic. In every farm he

visited, he was given a glass of our local wine for his effort—having

pedaled miles up and down hills and valleys on his old bicycle without

gears. We did not make fun of Bigoudi, as we would of other drunks, the

kind that staggered from the cafés after market on Friday afternoons,

who yelled at their horses and sometimes beat them. Bigoudi never

yelled, never insulted anyone. His alcoholism was his disease like the

tuberculosis affecting so many persons in our area. He was our crier

first; his alcoholism was his affliction and did not change our opinion

of him as a good man.

He carried in his pants pockets a tin can of bicarbonate of soda

from which he took a good mouthful after each drink. Our local wine is

called

vin gris.

It is a very acidic white wine made from the Pinot Noir variety of

grapes. The skin of the fruit is dark blue, but its flesh is pale green.

The wine is drunk as cool as possible. In the times of Bigoudi, no one

had refrigerators so it was brought up from the cool cellar before

drinking or put in the pail down into the well. It was consumed mostly

in summertime and was tart and refreshing. Also, it was very cheap. It

flowed on Friday afternoon at the end of our market days. There were

many cafés that were only the kitchens of people who owned a vineyard or

their relatives.

The press belonged to a cooperative of small growers, and it

would move from neighborhood to neighborhood at "crushing" time. It was

a small wooden press, the screw hand-carved from a tree trunk, usually

walnut, in our area. Men took turns in turning the press mounted on the

back of a wooden flat-bed chariot. The raw wine—really, grape juice—came

down via a small gutter protruding from the trough under the screw,

directly into a huge large bottle covered with wicker in the form of a

basket, easy to transport to the farm where the juice would go slowly

through its fermentation process. Barrels were sterilized by burning

sulfur sticks inside, slowly removing the oxygen and, therefore, all

aerobic bacteria. The yellow sticks of sulfur were held in suspension by

a large, deep, spoon-like piece of metal, whose handle reached outside

the barrel where it was fastened, a cork and cloth making the barrel

absolutely air-tight.

After the grape pressing was done and the juice sent to its

journey before becoming wine, a lot of residue—skins, stems—were left in

the trough under the screw. This unfermented residue was taken to the

"alambic"—the still—to be transformed into "eau de vie de marc". We

children would go to look at the beautiful machine, belonging to the

commune, all brass and copper, a long, horizontal cylinder with a burner

being constantly stoked with wood. It looked like the front end of a

locomotive, smoking, hot, shaking on its wheels, all of it immaculately

shining. On top was a long, spiraling glass tube, at the end of which

the raw alcohol would come dripping slowly into glass bottles. This was

the "eau de vie de marc," rare, precious, to bring back the sick to

health. Eugene, my grandfather's orderly and gardener, would tie a

bottle, carefully set on a little wooden platform in a pear tree so as

to enclose a just-forming pear. The pear would slowly grow inside the

bottle and, when matured, fall to the bottom of the bottle. You had then

a fully grown pear inside a bottle, the puzzle of many visitors who did

not understand how you could put a large pear into a small necked

bottle.

At the end of a day's work, he was often found asleep in a ditch,

his bicycle lying down on an abutment. Passing carriages would pick him

up and carry him and his machine back to his house. If no one came, he

just slept there. Bigoudi lived in the oldest part of the village known

as the "faubourg," a series of small stone houses set side by side, each

with only one door and one window. There was no electricity, no sewers,

and the only water available was at a public pump a few hundred yards

away.

In his unique position, wandering from farm to farm, he

encountered abandoned wheels, tires, metal objects, etc... Bigoudi was a

collector, and his house was said to be a real dump, which we did not

doubt, since he always wore the same dirty old clothes, summer and

winter.

A few days after the Allies landed in Normandy, everyone in the

village assumed that the war would soon be over. We all had visions of

American, English, Polish, Canadian soldiers parading through our

villages and towns. Under the direction of Mademoiselle Limousin, a

retired school teacher, we learned to sing "God Save the King," which

was the only song in English she knew. Looking through our old Larousse

dictionary (edition 1929), we found pictures of flags from every

country. We were put to work painting flags to string across the main

street when the Allies came marching in. America was to us the land of

plenty—plenty of soldiers, plenty of tanks and guns, planes, ships,

food, and liberty for all. We could not wait to receive the liberators,

and we strung up our line of paper flags (double-faced) across the road.

The liberators did not arrive when expected. From the few radios,

illegally kept from the authorities who had confiscated most of them, we

knew that the Allies were encountering fierce resistance and huge

casualties in Normandy.

It was Bigoudi who rushed into my grandfather's consulting room

to say that a German column was coming our way and we had better take

those flags down if we did not want to all be vaporized by guns and

flame-throwers.

One end of the rope was attached to the stove in my upstairs

bedroom and the other to Monsieur Thevenin's house across the street.

Eugene, my grandfather's orderly, was sent to untie the ropes and bring

down the flags. Eugene had been in the trenches with Grandpa in the

First World War and had come back to live in our town. He helped in

surgery, processed the x-rays, took care of the car, the garden, cleaned

the fireplaces, the gutters, the courtyard, while his wife Suzanne

worked with my grandmother in the house, cleaning, cooking, giving me my

weekly bath. They both lived in a small house with a big garden on the

outskirts of town. They came to work in our house every day except

Sunday. They had no children. Suzanne had had tuberculosis and my

grandfather had advised against parenthood, but they had been given, or

taken, the right to treat me as their daughter and they were the ones

who generally punished me when I had done something wrong. They kept a

cat-and-nine-tails whip in the kitchen that they used often on my

legs—gently. I knew that they loved me and I loved them as another set

of relatives.

Earlier on I had learned that they had the right to discipline

me. Eugene had given me quite a verbal and physical lashing after I had

snapped the heads of all the tulips in the flower garden—just to hear

the crack, the exciting sound. Complaining to Grandpa that Eugene had

beaten me, he replied "Good"—and that was that. Never to complain again

about what Eugene did to me—or Suzanne.

Eugene came downstairs with an armful of flags and ropes as three

German soldiers were ringing the doorbell. Suzanne was opening the door

painted with a big red cross on the right side. I was right behind

her—to see, as usual. The staircase to the upper floor came down in the

same corridor, fortunately dark. Eugene rushed into the surgery room and

hid the flags under the pad of the operating table.

This was 1944—after the landing. No more spic-and-span officers,

organized, clean, well-fed German troops. After the opening of the

eastern Front in 1941, we had seen the deterioration of the German army.

Most of their seasoned soldiers had been sent to the Russian Fron,t and

those left were young, very young, almost as young as I was, or old.

The three men at the door were young, dirty, disoriented. The one

in the middle, supported by his comrades, could not have been more than

16 years old and was the one in obvious pain, crying. No blood, though.

No visible wound. I do not know what Grandpa did to the soldier in

surgery but he said: "Poor kid—appendicitis. They understood that they

must take him to a hospital. I don't know if he'll make it in time. I

gave him a shot. What a waste!" When Eugene was changing the sheet on

the pad I saw the flag ropes and the corner of the Canadian flag—so

difficult to paint those sleeping lions—sticking out.

In less than 24 hours, the whole town knew that Bigoudi had saved

us—for the moment at least—from potential disaster. And he had not been

the one to spread the news. So Bigoudi was honored and feasted the usual

way. That day and for another week. A few more liters.

Bigoudi GGauthier Twins Pen Infanticide

Conversation Unclear Casino Threshold Michel Bombay

About Laure Acknowledgements Autrefois Go-top

Chateaumeillant, Cher, France 1936 - 1938

Monsieur Gauthier loved “his” titmice.

He had installed many birdfeeders in his beautiful garden. His

days, since his retirement as a mail carrier, were devoted to the upkeep

of his mini-paradise and its winged visitors. It would have been hard to

tell whether he had trained his avian friends or whether they had

trained him.

They flew toward him as he came out of his small house several

times a day to assure himself that the platforms and feeders he had

built throughout his garden were fully stocked with crushed seeds and

small cakes of suet.

His enemies, sworn enemies, were the neighborhood feral cats that

would come onto his property and lay in wait for a chance to catch one

of “his birds.” Mr. Gauthier was the self-appointed nurturer, defender,

protector of the birds in “his” domain. A war was on, and Mr. Gauthier

was determined to win it.

And he almost did.

First, he installed dangling bells in his fruit trees. Then, he

bought a stuffed dog that could only be put out on nice sunny days.

One day, Monsieur Gauthier bragged to my grandfather that he had

finally, definitely solved his “cat problem.” His solution was a

20-gauge. At dawn and at dusk, he would wait for the uninvited visitors

and dispatch them quickly to the status of former visitors. Mr. Gauthier

would then bury the dead animal at the foot of his trees, insisting that

it made perfect fertilizer.

Monsieur Gauthier was beaten by a flea from the body of an

“offender” and died of a plague-like ailment.

This was before the Second World War, before antibiotics had been

introduced to Europe. Mr. Gauthier had been a single man and left no one

to take care of “his birds.”

I had observed that most people either liked cats or dogs; my

grandfather did not like cats and definitely liked dogs, even loved

them. I inherited his inclination and spent a lot of time in the company

of dogs. There had never been a cat in my grandfather’s house, but there

were many dogs—retrievers, such as cocker spaniels, who were allowed in

the house and with whom I was allowed to play as I wished. Grandpa and

the cockers hunted small game, such as birds and rabbits.

The long-eared dogs, the Petits blaus de Gascogne, the

“little blues”, were kept apart and were used for hunting big game, such

as boars or bucks. These did not belong to Grandpa but to an association

of men who would hunt together. They were kept in a separate building in

the courtyard, and Monsieur Delebarre was in charge of their upkeep. He

exercised them every day in the fields and forest on the edge of town. I

was not allowed to go and play with them, but I often did. I could

always tell when Grandpa was out visiting patients, since his car was

not in the garage. That allowed me to sneak out to the doghouse, and

Monsieur Delebarre let me.

I found their ears irresistible and they seemed to enjoy my

caresses.

And their voices! Oh, yes, I loved their bark, deep bassos, “aooh,

aooh.”

Since Grandpa and his hunting friends were all doctors or

surgeons from other towns, all the dogs had been given medical terms as

names, all six of them., I remember Aspro and Ultra (for ultraviolet)

and X (for rayon X, French for x-ray).

I like to think that they had a good life, fulfilled their destinies.

Bigoudi GGauthier Twins Pen Infanticide

Conversation Unclear Casino Threshold Michel Bombay

About Laure Acknowledgements Autrefois Go-top

The Twins

Chateaumeillant, Cher, France 1938r,

France 1937-1945

Oh, yes, they had names. They were named Alain and Albert. But we called

them the twins because they were impossible to distinguish.

When very young, their father hung himself shortly after the

death of his wife from tuberculosis, so they had been brought up by

their paternal uncle and his wife. Since their uncle and aunt were

childless, it was natural that they had taken the role of parents.

This was before the war and the invention of antibiotics. Many

persons suffered from tuberculosis there and in the countryside; the

only treatment was a long and painful course of weekly injections of

air—yes, air—around the infected areas in the lungs, since the bacillus

is anaerobic. Success depended mainly on early detection. In the case of

the twin’s mother, her infection was very advanced, according to

Grandpa, who had been seen her shortly before her death.

Their uncle made harnesses and all things having to do with

horses and wagons, as well as mattresses. (In those days, when a couple

was married, they had a mattress made—a mattress that lasted a lifetime

and often more.) His shop, with living quarters above, was directly

across from the boys’ school, so the twins had only to cross the street

to attend classes. They were quiet, obedient, gentle boys and grew up

learning their uncle’s trade.

To the right of the shop was a vacant lot in which farmers would

park their wagons on market days. Next to this empty space were the

kilns, where limestone was blasted to become powder used in mortar for

construction or by farmers to add to their land, paint, fruit trees,

trunks, and walls against pests.

On the left side of the shop was a series of three houses: one

belonging to a notary; one to the headmistress of the girls’ school, the

feared Mademoiselle Chatelain; and the last one to Monsieur Laporte, one

of the three cobblers in town.

I told you before how all the houses in town touched each other